Architect proposes semi-underground living to cope with GCC's hot summers

FORWARD-THINKING approaches to designing homes in the Gulf, making them better suited to the region’s soaring temperatures, have been tabled by an expert in sustainable architecture.

One is literally groundbreaking, since it involves building homes partially below ground level.

Others go back to Bahrain’s architectural roots to revive practices long forgotten in the rush to build modern properties, but all aim to reduce reliance on air-conditioning – in turn slashing carbon emissions and helping people save money on electricity.

They have been drawn up by architect Noor Deraz based on research she conducted in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, which are feeling the heat from climate change.

She found basement-level dwellings could reduce temperatures inside homes by as much as 8C during summer, due to the cooling effect of the earth.

While Ms Deraz does not envisage people living underground, she does suggest incorporating lower ground floor levels.

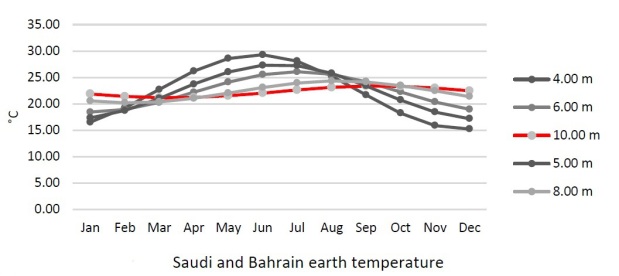

“I wanted to come up with an idea to bring cooling into the building without using electricity, so I studied the earth’s profile in Al Khobar and Bahrain,” Ms Deraz told the GDN.

“Because of the underground water, it stabilises the temperature.

“It’s between 20C to 22C underground in this region, which makes it a cooling atmosphere.

“I wanted to see how much temperature we could reduce and, on a normal summer day, it was 45C outside.

“By just going slightly underground, the temperature (of the dwelling) dropped to 37C.

“That was without adding ventilation, so it’s possible that it could have dropped to 32C.”

The findings are based on simulations conducted by Ms Deraz for her thesis while studying an MSc in Architecture and Environmental Design at Westminster University, in London.

Conference

She was invited to present her results last month at an international conference on sustainable urban development.

The Passive Low Energy Architecture (PLEA) conference took place in Edinburgh, Scotland, and brought together hundreds of experts in the field.

Other approaches outlined by Ms Deraz for the region include a return to traditional techniques largely abandoned due to widespread availability of air-conditioning, cheap electricity and modern construction trends.

That could be something as simple as a property’s orientation to reduce exposure to the sun, types of building materials, thickness of walls, use of courtyards to create a cooler environment and better ventilation exemplified by traditional wind towers.

“No-one told our ancestors there was a lot of sun on the south façade and that there needed to be a thicker wall there and no windows,” said Ms Deraz, an Egyptian who was born and raised in Al Khobar.

“They figured it out and knew they needed to build using cooling materials.”

However, Ms Deraz said such practices were phased out following the discovery of oil in the 1930s and the construction of Western-style compounds by companies such as Aramco and Bapco, which influenced local trends.

Yet she pointed to how structures built to traditional specifications were still effective against the heat decades later.

“When you go into these houses today they’re still standing and still work the way they’re supposed to,” she said.

“Those thick walls keep it cool, as do the wind towers, the orientation and the windows.

“The courtyard was essential in traditional architecture because it was shaded by the house surrounding it.”

In fact, Ms Deraz said resorting to renewable energy – such as solar panels to power air-conditioning – should be the “last step” when it came to thinking of ways to conserve power while keeping houses cool.

“We have to find out exactly where you’re oriented, where the north and south is on your land,” she explained.

“In summer we have the sun at an 88-degree angle in the sky, so you need to place your windows and ventilation accordingly.

“These all reduce energy consumption and are not expensive because, when you’re building a house, you can choose your orientation and where to put windows and doors.”

Meanwhile, the region’s harsh climate means approaches adopted elsewhere in the world are not viable.

“Sustainable architecture in general suits your environment and climate,” said Ms Deraz.

“What’s sustainable here isn’t what’s sustainable in England or in Brazil.

“It’s whatever allows you to reduce energy consumption, CO2 emissions, co-operate with your environment and spend more time outdoors.”

She says such designs can still incorporate luxurious features that many in the region have grown accustomed to, but acknowledged public awareness was needed – as well as social acceptance of new, or reinvented, concepts – so people could make informed choices when it came to designing homes.

“It’s a matter of showing people how much money they’ll save (through sustainable architecture),” she said.

“But you have to be able to show them graphs, which means you need studies and expertise.”

Source: http://www.gdnonline.com/Details/246187/Cool-homes-plan-for-a-hot-climate-